We've all heard the analogies. Someone's trying to explain some aspect of software development and they inevitably compare the process to... building a house. You've probably done it. I've done it more times than I can count. And with certain examples, the analogy might be helpful. But overall, I've become convinced that this false equivalence is downright harmful. Why??? Because software development isn't much like construction at all. It actually has far more in common with healthcare.

This isn't just semantics. I believe that, if more people could apply the proper paradigms to software development, they'd get far better results from the process. Framing a software project in construction terms isn't just misguided. It could very well lead you to mismanage the project altogether - and anger those who are working so hard to make it a success.

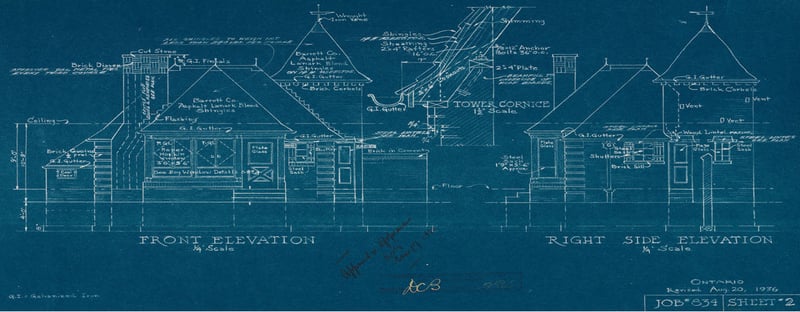

Throw Out Your Blueprints

So much effort is wasted on chasing the fever dream of the "flawless spec" (blueprint). This (misguided) idea implies that if you could just craft the perfect set of requirements, you could then simply hand that blueprint to the dev team, and they could crank out the app exactly as you'd planned it, as though they're coding automatons. But this ideal is broken.

A detailed blueprint implies that the stakeholders know what they want. A bloated spec, chock full of reams of minute requirements, implies that the stakeholders absolutely positively know, beyond any shadow of a doubt, exactly what they want.

After slinging code for a quarter century, I can confidently tell you that I have never met a single stakeholder who truly, fully, completely knows what they want. Not one.

Of course, they have strong ideas about what they want. And they may have already done a great deal to define every aspect of the proposed app. But I can guarantee you that they don't 100% know what they want before we start writing the code.

Because, once they start seeing the screens in front of them, and they start playing with the features that have been completed up to this point, they inevitably start realizing that their original vision was, at best, incomplete. At worst, it may have been outright wrong.

You see, there's a name for software that can be 100% quantified. It's called a finished product. So unless you plan to perfectly copy a pre-existing system, there's no way that you've absolutely defined all the specs for your new project upfront.

Your home was probably built from pre-defined blueprints that were developed months or years ago. They've been used for other houses that look just like yours. And the process of building your house is truly part of a repeatable cycle. They print out another copy of the same blueprints. They may even hire the same workers. And in a predictable period of time, they can spit out another house just like the others that they've previously built.

But when you're building a brand new app from scratch, there is no such thing as a perfectly-defined, cookie-cutter development process. If you're paying a team to build custom software, it's because, on some level, you need something that's truly unique to your needs. And as long as that's the case, you won't ever be able to just hand the blueprints over to the dev team and know that they'll crank out your app 100% to-spec in a few months.

This "every-project-is-a-little-different" quality doesn't readily lend itself to construction. But it is a solid way to describe the process of providing healthcare.

You Can't "Dumb Down" Programming

In medicine, there's really no such thing as a "routine" procedure. There are just procedures that have extremely-high success rates with low likelihoods of complications - and there are procedures with much lower success rates and much higher likelihoods of complications.

Even a "routine" procedure can become quite risky if the patient has other complicating factors. It doesn't matter how many tomes are dedicated to medical procedures. There will never be a day when you can hand a set of pre-defined "specs" to a junior brain surgeon and be confident that he'll be able to successfully complete the surgery with no supervision.

I've noticed many trends in corporate America where there's an implied desire to make application development like some kind of assembly line. You stuff the detailed instructions in the front end. And eventually, your new app comes shooting out the back end. But once you realize the parallels with healthcare, you need to ask yourself: When YOU are going under the knife, do you want to put your faith in an instruction manual? Or do you prefer to trust the training and the experience of those who are performing the surgery??

Meet Your Devs

It may sound silly (or arrogant) to compare a programmer to a surgeon. For most of my career, I wouldn't have done it. Then a funny thing happened to me: I tried to teach someone else - a complete novice - to code. That's when I first started to appreciate the sheer volume of highly-specialized knowledge I'd packed into my brain.

The nature of my work may be nowhere near as important as a doctor's. But I'm pretty confident that the volume of technical info floating inside my head is comparable to a surgeon's.

I'm highly proficient in at least five different programming languages. I have reasonable experience in several others. I'm proficient-to-expert level in many other "supporting" technologies like HTML, CSS, SQL, REST, SOAP, GraphQL, etc., etc. I can develop in mobile, web, or console platforms. I can flip comfortably between frontend, backend, and middleware technologies.

The point here isn't to brag about my resume. The point is that when you start quantifying all of the technical details I know, across all of the platforms in which I can operate, it constitutes a metric crap-ton of knowledge. And I'm not just talking about myself.

Do a deep dive with nearly any dev who's been in this game for a decade-or-more and you're likely to find a comparable (or greater) level of knowledge. Work this career for long enough and you'll accumulate a staggering library of critical data.

It's not arrogant or boastful to state that many devs are as highly skilled in their field as surgeons are in theirs. And yet, it often feels to me like "the business" keeps looking for ways to relegate programmers to being assembly line workers.

Diagnosing

If I have a detailed set of specs that explain exactly how I'd like to have a cabinet built, I could probably take those specs to a skilled carpenter and, for the right price, receive a fully-built cabinet in a reasonable period of time. That's how many organizations try to approach application development. They want to just shove the specs in your face and say, "Here. Build this."

Now imagine that I schedule a first-time visit with a physician. When I walk into the office, he asks the reason for the appointment. I give him a big pile of medical documents that explain how to do a particular medical procedure.

I ask him how soon he can perform this procedure on me. I also tell him that I need a detailed estimate on the cost.

He wants to know why I want this particular procedure. He wants to know what symptoms I'm experiencing. He wants to know all sorts of pesky details about my medical history.

But I brush all of this off and I just keep pointing at the medical "specs" that I've given to him. I tell him that he just needs to deliver the medical care as I've outlined it in the specs. How well do you think that appointment will turn out??

The physician isn't there to serve up medical procedures as though you're ordering them off a menu. The physician is there to solve problems. Any skilled physician is a problem-solver first, and a medical practitioner second.

Even if we assume that my ridiculous demands are correct, it would still be irresponsible for any physician to perform the procedure without first understanding the problem. But too often, we hand specs to devs, expecting them to deliver a product without properly understanding the problem that product is designed to solve.

Think I'm being dramatic here? Consider that quite recently I had to deal with a client who kept changing specs on me. They kept making arbitrary requests in the 11th hour of the project that had very real technical consequences. And with every new request, I kept asking, "What is the problem that we're trying to solve with these changes?" But they didn't really want to talk to me about problem-solving. They just wanted to talk to me about the specific request.

If I understood the problem, I could properly consult on the best options to solve that problem. But if I'm routinely kept "in the dark", it hamstrings my ability to be a proper problem solver.

Emergency Techs

Doctors don't grill you for information because they want to make you uncomfortable. They try to gather all relevant data because it vastly reduces the likelihood of emergencies - and helps them respond better when those emergencies occur. Experienced devs are very similar.

No matter how glorious your specs may be, the simple fact is that, once I get nose-down on the project, I'm gonna run into... something. Something unexpected. Something that alters the original goals of the project. Something that alters the timeline. Something related to ugly legacy code. Or something related to an uncooperative vendor. Doesn't matter what that "something" is. On any sizeable project, there's always... something.

When organizations try to insulate programmers from the process of building applications, they leave themselves poorly equipped to handle these emergencies. They tie the developer's hands and force the triage process through committees and reviews - and the project suffers for it.

I've had many scenarios when I encounter some kinda unplanned hurdle during the project. More often than not, I can quickly assess what's wrong, and I usually know exactly what should be altered in the project to solve the unforeseen issue. But I can't actually fix it. Because, even after a quarter century in the career, I often find myself without the authority to make that call.

So I ping my PM and explain the issue. The PM calls a meeting with our client POC. The client POC calls a meeting with all the project stakeholders. Sometimes it even requires another meeting to specifically loop in the client's "leadership". Frequently, I'm pulled into every one of these meetings, to repeatedly explain the issue to the latest set of actors.

After weeks of back-and-forth (sometimes, months), the client finally makes an official decision on how to handle the issue. It's usually identical, or extremely similar, to my initial recommendation. And once everyone has signed off on the change, I can finally get back to work on the project.

If that project were a patient, the patient would have long-ago expired.