It is really common nowadays for development teams to hurry in order to meet deadlines. One of the first things put aside is the quality of the code in general, but one point that is among the most important ones, and after some years on the market I can clearly state is the first to be put aside, is security.

The aim of this article is to raise awareness among our community on how a development process is something that needs to be done at its right pace and with developers concentrated in what really implies to build secure software. I will try to explain some of the processes involved in an eventual attack to show developers some ideas of how their code could be used in someone else’s advantage.

Reverse engineering an iOS Application

[Disclaimer: I will just describe the processes and mention tools and details, but this is not intended to be a guide on how to do any of this and I will not get into details regarding the environment setup.]

The target

Let’s get hands on as if we were the attacker, first thing to do is find the target and start looking for vulnerabilities. A target would be an actual app, the .ipa bundle file, but it’s not enough with just downloading it from the App Store. Apple encrypts all apps, so the first step would be to decrypt the bundle file. In iOS 12 for example this can be done with frida, the result will be a decrypted .ipa file. Basically what you can find inside is the binary file of the actual code, and all the files included in the bundle. For example, assets, property list files (.plist), JSON files and any other file the developer added. Now, we are ready to start what is called Static Analysis.

Static Analysis

This is the process of inspecting the files we got on the previous step and look for possible vulnerabilities. Let me first make a line between “bundle files” and the application binary itself (where the code is), first let’s look at bundle files.

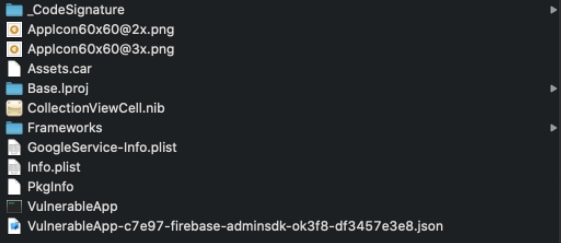

In the next image you will see how a simple little app bundle files could look like:

As you can see we already have some files that look familiar to us: Info.plist, GoogleService-Info.plist, a .json file apparently related to firebase configuration, a frameworks folder… Any ideas already? First thing to note is that access to these files is a really easy task, so any information stored here is in the hands of anybody. Let’s hope there aren’t any private keys stored there or SDK configuration keys. It wouldn’t be rare either to find other configuration files that could give you lots of hints on different behaviours of the app, for example, feature flags.

As you can see we already have some files that look familiar to us: Info.plist, GoogleService-Info.plist, a .json file apparently related to firebase configuration, a frameworks folder… Any ideas already? First thing to note is that access to these files is a really easy task, so any information stored here is in the hands of anybody. Let’s hope there aren’t any private keys stored there or SDK configuration keys. It wouldn’t be rare either to find other configuration files that could give you lots of hints on different behaviours of the app, for example, feature flags.

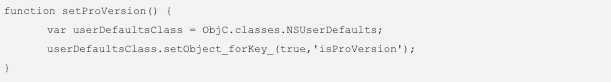

What if we find this?

We can guess that there is some code that is not supposed to be executed yet and that there is a check for that on the client side in a particular case maybe.

The Info.plist is also a great source of information, some capabilities enabled in the app are here, for example NSAllowsArbitraryLoads (enables weak TLS settings on some domains) and CFBundleURLTypes which will describe custom Scheme URLs commonly used to let other apps launch yours through a URL (which is almost certainly parsed on the client  ).

).

Looking again at our Bundle Files, we can see a Frameworks folder, there you can find bundle files for frameworks included in the target, and easily get which versions it’s using. For example there was a case of a vulnerability that affected lots of projects in a version of Alamofire, more on this here.

Now let’s see what we can get from the application binary, first we will use a tool called class_dump_z. As its name states, we can dump all the classes to a file and start digging into names that call our attention. Next thing, to go a bit deeper in the code, could be disassembling and decompiling the binary, for this matter we can use two tools: hopper or ghidra. Both are similar and what they will do is to let you see the decompiled code in different ways (Assembly, pseudocode, hexadecimal, control-flow graph).

For example here you can see the pseudo code (in hopper) of a viewDidAppear method:

As you can see r4 is a reference to NSUserDefaults, and the if on the next line gets the value for isProVersion in NSUserDefaults and executes an specific code depending on it.

As you can see r4 is a reference to NSUserDefaults, and the if on the next line gets the value for isProVersion in NSUserDefaults and executes an specific code depending on it.

At this stage we should gather all the information we can in order to have some stuff to do in what is called Dynamic Analysis.

Dynamic Analysis

This is the last process i will describe because here is where we already have actual control on what we can do with the app itself, and we can finally write code and see if the app is vulnerable.

Imagine we found that the target uses Scheme URLs (we saw the CFBundleURLTypes in the Info.plist), now that we have access to the code, we can look for the code that handles the scheme URLs, this is method application:openURL:options: method from AppDelegate class:

Assuming r19 contains the URL coming from “the outside” (could a browser in your iPhone), this url should be something like “yourApp://”. If we analyse this code, we get that if the URL contains “news” it will then remove “news/” occurrences, instantiate a WebViewController and configure it with the URL, that by the name of the method configureWithHTMLString we know it expects HTML. So there is a hint on how an HTML script could be executed on this app just by pasting some encoded URL in your browser, yes, now any javascript code could be executed within this WebViewController. For example, if i find an encrypted database in the bundle, and i find that the key to decrypt key is in the Info.plist file, i could write an HTML script with a Javascript function to open that database file and post it to a remote server or whatever you want to do with it.

Assuming r19 contains the URL coming from “the outside” (could a browser in your iPhone), this url should be something like “yourApp://”. If we analyse this code, we get that if the URL contains “news” it will then remove “news/” occurrences, instantiate a WebViewController and configure it with the URL, that by the name of the method configureWithHTMLString we know it expects HTML. So there is a hint on how an HTML script could be executed on this app just by pasting some encoded URL in your browser, yes, now any javascript code could be executed within this WebViewController. For example, if i find an encrypted database in the bundle, and i find that the key to decrypt key is in the Info.plist file, i could write an HTML script with a Javascript function to open that database file and post it to a remote server or whatever you want to do with it.

Let’s go now with the last flaw, do you remember that code with a check for the bool value of “isProVersion” stored in NSUserDefaults that we found during the static analysis? Well let’s see how we could be Pro without really being it, it’s actually pretty simple. We will make use of frida again, and by simply writing the code we need in a .js file and launching the tool, we are done.

Being this our setProVersion.js:

We can run frida -U -l setProVersion.js VulnerableApp and there is your true value for the isProVersion key injected in the app.

We can run frida -U -l setProVersion.js VulnerableApp and there is your true value for the isProVersion key injected in the app.

Conclusion

I must say it’s scary to see how most of the apps in the AppStore have at least one of these vulnerabilities, maybe with not much to take advantage of, but as i said at the beginning this aims to raise consciousness.

It is really common to unintentionally introduce security flaws, and not only developers but whole teams should be aware of this, because some of the flaws involve the whole infrastructure design of a system.

The post Security awareness in an iOS environment appeared first on Apiumhub.